“Hell Upon Earth”: The Andersonville Prison Lithograph

“The scene of indescribable confusion among the prisoners presents them in every imaginable position, standing, walking, running, arguing, gambling, going to or coming from the Branch with cups, dippers, canteens, or rude pails with water, lying down, dying, praying, giving water or food to the sick, crawling on hands and knees, or hunkers, making fires and cooking rations, splitting pieces of wood almost as fine as matches, the sick being assisted by friends, others “skirmishing for graybacks”, washing clothes and bodies in the Branch, trading in dead bodies, fighting, snaring, shouting …”. Excerpt from History of O’Dea’s Famous Picture of Andersonville Prison by Thomas O’Dea, 1887

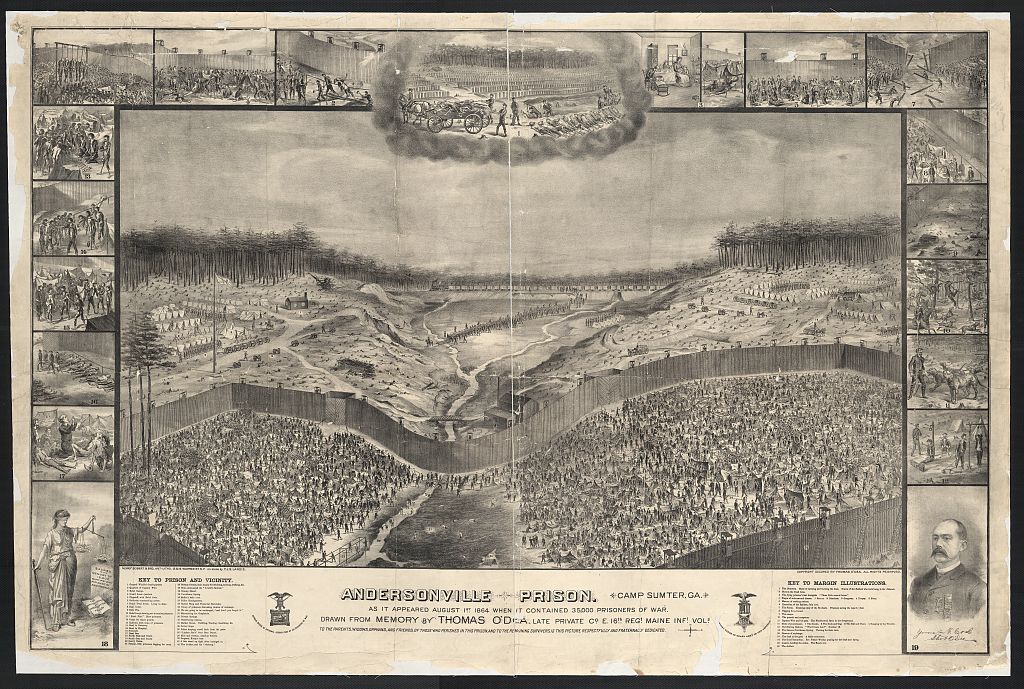

The Andersonville lithograph, which measures 40 x 60 inches

The Andersonville lithograph, which measures 40 x 60 inches

In the Memorial Hall of the Fifth Maine Museum hangs an oversized lithograph that can be overwhelming to take in all at once. Hundreds of tiny figures fill the three and a half by five foot print. As your eyes adjust to the scene, details emerge and your heart sinks, because what is depicted can truthfully be described as a vision of hell on earth.

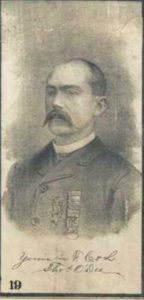

Thomas O’Dea, artist

Thomas O’Dea, artist

Officially titled Andersonville Prison. Camp Sumter, GA. As It Appeared August 1st, 1864 When It Contained 35,000 Prisoners of War, the poster was created by Thomas O’Dea (c.1848-1926), an immigrant from Ireland who enlisted in the 16th Maine Regiment in 1863. O’Dea was captured in May 1864, and ended up at Andersonville Prison that summer. He was 16 years old.

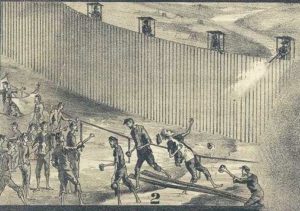

“Shot at the Dead Line”

Andersonville was synonymous with the worst of wartime atrocities. The statistics are staggering. Built to house 10,000 prisoners of war, 35,000 soldiers were there when O’Dea arrived. Over 13,000 prisoners died during the 15 months the prison operated. Over forty percent of all Union prisoners of war who died in captivity died at Andersonville. Captain Henry Wirz, the prison commander, was the only Confederate soldier executed for war crimes at the end of the War. The presiding judge at Wirz’s trial pronounced, “his work of death seems to have been a saturnalia of enjoyment for…[Wirz], who amid these savage orgies evidenced such exultation and mingled with them such nameless blasphemy and ribald jest, as at times to exhibit him rather as a demon than a man.”

Captain Wirz and his pets. The Bloodhound, Spot, in the foreground.

These demonic brutalities are depicted in O’Dea’s lithograph in precise detail. All the basic necessities of life were in short supply or totally absent. There was little shelter, and very little food and clean water. Prisoners slept in holes they dug in the ground, covered with scraps of cloth if they could find them. The men wore rags, and many were nearly naked under the hot Georgia sun. Injured or ill soldiers died without medical attention of any kind. In these terrible conditions, men turned on each other, and the strong preyed upon the weak and sick. It was “Hell upon Earth,” the survivors said.

“Swamp, with Prisoners digging for roots”

O’Dea lived and was released from Andersonville in February 1865. By 1879 he was married and living in Cohoes, New York. Aggravated at what he thought were inaccurate depictions of Andersonville, he began drawing, in pencil, the camp from memory on the wall of his home. Completed in 1885, the 9-foot-long drawing became locally famous, and by 1887 he had set up a business and sold 10,000 copies of the drawing as a lithograph at $5 each. It was a best seller, and defines people’s image of Andersonville to this day.

The Cemetery. Mode of Carrying and Burying the Dead.

Graves of the Raiders who were hung in the distance.

One of those lithographs ended up at the Bosworth Post Grand Army of the Republic hall in Portland, Maine, and was later given to the Fifth Maine Museum when the post’s building was demolished in the mid-1970s. It is one of the museum’s most popular and thought-provoking artifacts.