Wabanaki on Peaks Island

The New World Wasn’t New

“Between 1500 and 1800, roughly two and a half million Europeans moved to the Americas… and as many as 50 million Native Americans died, chiefly of disease…”

Jill Lepore

Peaks Island was inhabited when Italian explorer Verrazzano sailed up what is now the Maine coast in 1524. The islands were the home of the Wabanaki people and their ancestors, who have inhabited the land for at least 13,000 years, or longer according to oral tradition. They were a place for native people to gather food, hunt, and fish. Their territories were fluid, but well-established when Europeans arrived. The Wabanaki were also skilled farmers. A cornfield in western Maine measured 700 acres – nearly the size of Peaks Island. They maintained trade routes with other native groups both north and south. The land was well-managed by the Wabanaki that lived in Maine at the time of first contact. Their lives depended on unrestricted access to it.

After Verrazzano’s voyage, word spread about the riches of the eastern seaboard of what would become America. By 1600, hundreds of European fishing and fur trading vessels were visiting the New England coast annually. These fishermen used the Gulf of Maine islands, including Peaks, to process and salt huge amounts of codfish to take back to Europe. They took the cod but inadvertently left behind disease, including smallpox and measles, which the native people had no immunity to.

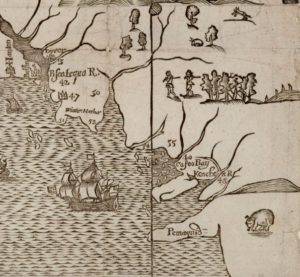

Detail from Woodcut “Map of New England,” published in The Present State of New-England, William Hubbard, (1677), Massachusetts Historical Society.

Detail from Woodcut “Map of New England,” published in The Present State of New-England, William Hubbard, (1677), Massachusetts Historical Society.

This detail shows the Casco Bay islands at the time of King Philip’s War.

The Great Dying

“There is a great many of the Indians dead this year both east and west of us and [a] great many die still to the eastward from us.”

-John Winter, Richmond Island trade station off Cape Elizabeth, 1634

By the time permanent European settlements were established in the early 1600s, the land looked empty. And, by then, it was — or nearly so. Up to 90% of the tens of thousands of Wabanaki people died from disease between 1616 and 1619, a period called “The Great Dying.” Pandemics continued throughout the 1750s. The native people who survived The Great Dying were weakened and traumatized, and had to regroup to protect their access to the land that sustained them. Tribal groups broke down, relocated, and merged together for survival.

Anglo-Abenaki Wars in Casco Bay

“The prosperity of the town [Portland] was retarded by the frequent wars with the French, into the spirit of which…our people heartily entered. They were Englishmen, and hated…the French, the Indians, and the Devil; these were the Trinity of evil.”

Edward Elwell, 1876

Relations between the Wabanaki and the Europeans were complex, and reflected conflicts playing out in Europe, particularly between the English and the French. Some settlers treated the native people fairly, but many did not. Decimated by disease and losing access to their land, the Wabanaki grew increasingly desperate, and were drawn into the struggles playing out around them. Misunderstanding arose around land deals and fur trading. Kidnapping natives into slavery was common in the immediate post-contact period. 58 natives were taken from the coast of Maine in 1525 and enslaved. Explorer George Waymouth kidnapped 5 native men from Pemaquid in 1605.

Distrust was multiplying on both sides, and trouble was brewing. Peaks Island and Casco Bay were at the center of these terrible events.

From 1675 until 1760, six devastating wars between Natives and Europeans kept Maine, the borderland between New England, New France, and the Abenaki/Wabanaki homelands in turmoil for nearly a century. King Philip’s War of 1675-76 was the deadliest war in American history, per capita. Multiple battles were fought in and around Portland (then called Falmouth, which was thriving before the wars), and the Casco Bay islands, including Peaks, House, Cushing, and Jewell.

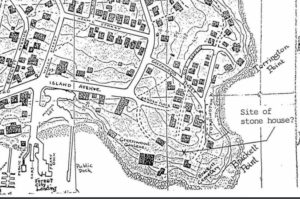

On Peaks, the so-called “Stone House” was built before 1670. Located near what is now the Brackett Cemetery and facing the harbor, it was the site of two major incidents. In 1675 the Palmer family was either killed or driven away from the Stone House where they were living – accounts differ. A deadly skirmish the following year killed seven European men who had taken refuge in the Stone House after coming to the island to find food for their families, who were hiding out on Cushings Island, and close to starvation. Only one man is named: George Felt Jr. Felt had a fraught history with the Wabanaki, including a series of land disputes. Accounts of the time describe him as “more active than any man in those parts against the Indians,” which, from the native perspective, was bad news. The number of native casualties in these events isn’t noted in the historical record.

Possible location of the “Stone House” on Peaks Island, circa 1670

Possible location of the “Stone House” on Peaks Island, circa 1670

(detail from Sudlow, Lynda, “An Examination and Analysis of Brackett Cemetery Gravestones (1794? – 1966): Peaks Island, Maine.” (1991))

Peaks once again saw action in 1689, during King William’s War. Several hundred people gathered on the island to prepare to once again attack settlements in Falmouth, which they did in September 1689. At least one captive European woman was detained by the natives on Peaks at this time: Esther Waldron Lee. Lee described seeing at least 80 war canoes, and a mix of Native and French people.

These were nightmarish conflicts. Women and children were killed. Captives were tortured and the dead mutilated. Kidnappings were routine. Entire settlements – both European and Wabanaki — were wiped out. It took generations for European towns to re-establish themselves. Many Wabanaki were killed, or died from starvation. Constant tensions kept them from hunting and growing food. They often went “underground,” giving up their cultural practices and communities in order to survive by blending in with the colonists. The destructive results of early English settlement can still be seen when you look at a map of present-day Wabanaki communities, which cluster to the east and northern parts of the state and not in in southern and western Maine, where they once thrived.

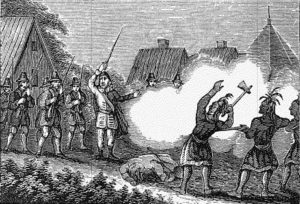

Woodcut depicting 17th century conflict between Europeans and Native Americans (Wikipedia)

Woodcut depicting 17th century conflict between Europeans and Native Americans (Wikipedia)

Ultimately the English settlers prevailed, although Portland was basically abandoned until 1715, and Peaks only had three families by 1775. There are at least a dozen very early fieldstone markers in Brackett Cemetery, without any inscriptions that likely pre-date the use of the cemetery by the Brackett family. It has been suggested that these mark the graves of those killed there in 1675-1676.

Since the turn of the 20th century, very little has been written about the Anglo-Abenaki Wars in Casco Bay. These early accounts are, unsurprisingly, lopsided in favor of the European settlers. The native people are described as “brutes,” and “savages,” and the English settlers as “brave” and “defenseless.” The actual history is much more complex, and deserves a re-examination.