Fifth Maine Museum - Peaks Island

History. Legacy. Community.

The Fifth Maine Regiment Memorial Hall was built in 1888 by the civil war veterans of the Fifth Maine Volunteer Regiment as a memorial and reunion hall. As time passed, the reunions grew smaller and smaller, and the building fell into disrepair.

In 1956, The Fifth Maine Regiment building was given to the Peaks Island community by the descendants of the veterans who built it. Since then, restoration work has brought the building back to its former glory. It is an architectural gem that is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, the building houses the Fifth Maine Museum, a museum that tells two intriguing and related stories: the history of Peaks Island from its days as “The Coney Island of the North” to its role in World War II, and the story of the Fifth Maine Regiment.

Collection and Exhibits

-

Defending the Coast

Defending the Coast: Warfare in Casco Bay is a semi-permanent exhibit that opened in May 2024. This exhibit explores Peaks Island's role in Casco Bay's harbor defense system that lasted for centuries. Until World War II, defending the coast was the priority. Deep-water ports, like Portland, facilitated trade, and healthy trade equaled a healthy economy. Islands and harbors were strategic locations when it came to defending the coastal cities along the eastern seaboard. Come and learn about the fortifications that dot Portland Harbor to this day.

-

The Memorial Hall

The Memorial Hall looks much like it did when the 5th Maine veterans used it for their annual meetings. The space features stained glass windows and civil war relics collected by the veterans as well as new exhibits displaying items from the museum’s collection.

-

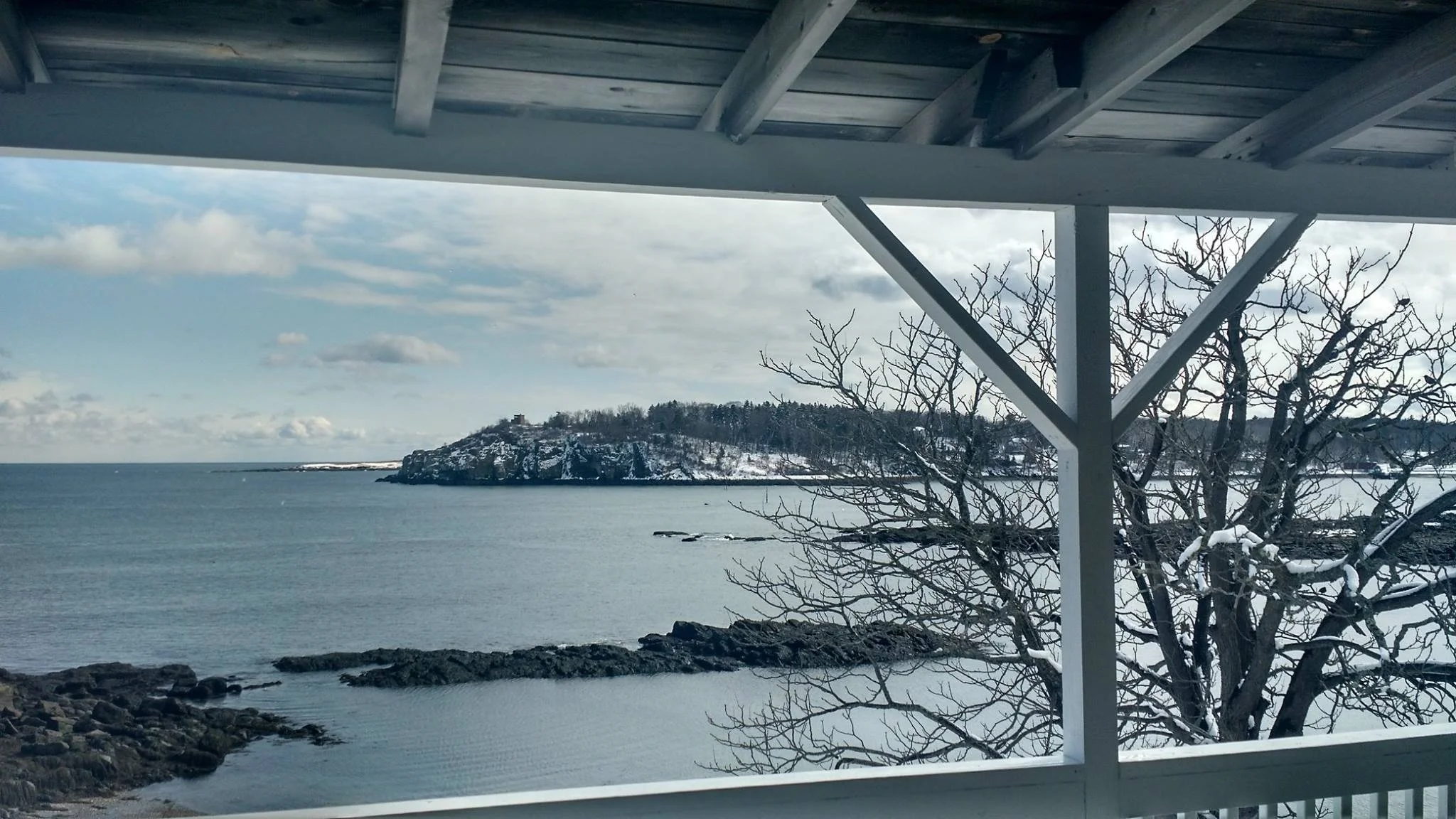

Keeping Warm and Keeping Busy: Winter on Peaks Island

Keeping Warm & Keeping Busy - Winter on Peaks Island is a cheerful exhibit that explores what winter was like on Peaks Island. See over 30 images of the island in wintertime, learn about the importance of ice harvesting on the island, and explore the ways in which islanders kept busy during the coldest and quietest months of the year.

The 5th Maine Today

Our mission is to preserve and promote the history of Peaks Island and the legacy of the Fifth Maine Civil War Regiment for the education and enrichment of the community. Our iconic building is where history and community come together.

The Fifth Maine in Photos

We open for the 2025 season on May 23!

Announcements

Hours

We are open:

From July 1 - August 31, we are open every day from 10am-3pm.

In the shoulder seasons (May 23-June 30 and Sept 1-Oct 9) we are open only on Fri, Sat, Sun, and Holidays.

We can also open by appointment!

Events